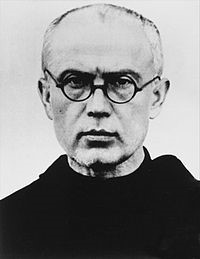

Saint Maximilian Kolbe was a Polish Conventual Franciscan Friar. During the German occupation of Poland, he remained at Niepokalanów a monastery which published a number of anti-Nazi German publications. In 1941, he was arrested and sent to Auschwitz, where in terrible circumstances he continued to work as a priest and offer solace to fellow inmates. When the Nazi guards selected 10 people to be starved to death in punishment, Kolbe volunteered to die in place of a stranger. He was later canonised as a martyr.

Saint Maximilian Kolbe was a Polish Conventual Franciscan Friar. During the German occupation of Poland, he remained at Niepokalanów a monastery which published a number of anti-Nazi German publications. In 1941, he was arrested and sent to Auschwitz, where in terrible circumstances he continued to work as a priest and offer solace to fellow inmates. When the Nazi guards selected 10 people to be starved to death in punishment, Kolbe volunteered to die in place of a stranger. He was later canonised as a martyr.

Early Life

Raymund Kolbe was born on 8 January 1894 In Zdunska Wola, in the Kingdom of Poland (then part of the Russian Empire). His father was an ethnic German and his mother Polish. His parents were relatively poor, and in 1914 his father was captured by the Russians and hanged for his part in fighting for an independent Poland.

Raymund developed a strong religious yearning from an early life. He recounts an early childhood vision of the Virgin Mary. This vision was significant because he chose both the path of sanctity and also to follow the path of a martyr.

“That night, I asked the Mother of God what was to become of me, a Child of Faith. Then she came to me holding two crowns, one white, the other red. She asked me if I was willing to accept either of these crowns. The white one meant that I should persevere in purity, and the red that I should become a martyr. I said that I would accept them both.” [1]

Aged only 13, Kolbe and his elder brother left home to enrol in the Conventual Franciscan seminary in Lwow. This seminary was in Austria-Hungary and it meant illegally crossing the border.

In 1910, he was given the religious name Maximillian and was admitted as an initiate. He took his final vows as a monk in 1914. After a short period in Krakow, Poland, Kolbe went to study in Rome, Italy. He gained a doctorate in philosophy at the Pontifical Gregorian University in 1915. In 1919 he also gained a doctorate of theology from the University of Saint Bonaventure.

Kolbe was ordained as a priest and after completing his studies returned to the newly independent Poland in 1919. He settled in the monastery of Niepokalanów near Warsaw. Towards the end of his studies, Kolbe suffered his first bout of tuberculosis and he became quite ill, often coughing up blood; the illness disrupted his studies. Throughout the rest of his life, he experienced poor health, but never complained, seeing his illness as an opportunity to ‘suffer for Mary’.

Kolbe was an active priest and particularly keen to work for the conversion of sinners and enemies of the Catholic Church. During his time in Rome, he witnessed angry protests by the Freemasons against the Vatican. Kolbe had a strong devotion to the Virgin Mary and he became an active participant in the Militia Immaculata or Army of Mary.

“I felt the Immaculata drawing me to herself more and more closely… I had a custom of keeping a holy picture of one of the Saints to whom she appeared on my prie-dieu in my cell, and I used to pray to the Immaculata very fervently” (Link Militia of the Immaculata)

He felt a strong motivation to ‘fight for Mary’ against enemies of the church. It was Kolbe who sought to reinvigorate and organise the work of the MI (Militia Immaculata). Kolbe helped the Immaculata Friars to publish high pamphlets, books and a daily newspaper – Maly Dziennik. The monthly magazine grew to have a circulation of over 1 million and was influential amongst Polish Catholics. Kolbe even gained a radio licence and publicly broadcast his views on religion. Kolbe was successful in using the latest technology to spread his message.

As well as writing extensive essays and pieces for the newspaper, Kolbe composed the Immaculata Prayer – the consecration to the immaculately conceived Virgin Mary.

Kolbe in Japan

In 1930, Kolbe travelled to Japan, where he spent several years serving as a missionary. He founded a monastery on the outskirts of Nagasaki (the monastery survived the atomic blast, shielded by a mountain). Although the location on the side of the mountain was strange, its position helped it to survive the later Atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki. He also entered into dialogue with local Buddhist priests and some of them became friends. However, increasingly ill, he returned to Poland in 1936.

Second World War

At the start of the Second World War, Kolbe was residing in the friary at Niepokalanow, the “City of the Immaculata.” By that time, it had expanded from 18 Friars to 650 Friars, making it the largest Catholic house in Europe.

When Poland was overrun by the Nazi forces in 1939, he was arrested under general suspicion on 13 September but was released after three months. When first arrested he said:

“Courage, my sons. Don’t you see that we are leaving on a mission? They pay our fare in the bargain. What a piece of good luck! The thing to do now is to pray well in order to win as many souls as possible. Let us, then, tell the Blessed Virgin that we are content, and that she can do with us anything she wishes” (Maximilian Mary Kolbe, source).

On being released, many Polish refugees and Jews sought sanctuary in Kolbe’s monastery. Kolbe and the community at Niepokalanów helped to hide, feed and clothe 3,000 Polish refugees, (of which approximately 1,500 were Jews). In 1941, his newspaper “The Knight of the Immaculate” offered strong criticism of the Nazis.

“No one in the world can change Truth. What we can do and should do is to seek truth and to serve it when we have found it. The real conflict is the inner conflict. Beyond armies of occupation and the hecatombs of extermination camps, there are two irreconcilable enemies in the depth of every soul: good and evil, sin and love. And what use are the victories on the battlefield if we ourselves are defeated in our innermost personal selves?”

“Christian Martydom and Political Violence, Google Books[3]

Although Kolbe did not write this, it is believed this was a factor that led to his arrest.

Kolbe in Auschwitz

Shortly after this publication, on 17 February 1941, he was arrested by the Gestapo for hiding Jewish people. After a brief internment in a notorious Polish prison, he was sent to Auschwitz concentration camp and branded prisoner #16670.

Shortly after this publication, on 17 February 1941, he was arrested by the Gestapo for hiding Jewish people. After a brief internment in a notorious Polish prison, he was sent to Auschwitz concentration camp and branded prisoner #16670.

Kolbe was sent to the work camp. This involved carrying blocks of heavy stone for the building of the crematorium wall. The work party was overseen by a vicious ex-criminal ‘Bloody Krott’ who came to single out Kolbe for particularly brutal treatment. Witnesses say Kolbe accepted his mistreatment and blows with surprising calm.

Despite the awful conditions of Auschwitz, people report that Kolbe retained a deep faith, equanimity and dignity in the face of appalling treatment. On June 15, he was even able to send a letter to his mother.

“Dear Mama, At the end of the month of May I was transferred to the camp of Auschwitz. Everything is well in my regard. Be tranquil about me and about my health, because the good God is everywhere and provides for everything with love. It would be well that you do not write to me until you will have received other news from me, because I do not know how long I will stay here. Cordial greetings and kisses, affectionately. Raymond.”

On one occasion Krott made Kolbe carry the heaviest planks until he collapsed; he then beat Kolbe savagely, leaving him for dead in the mud. But fellow prisoners secretly moved him to the camp prison, where he was able to recover. Prisoners also report that he remained selfless, often sharing his meagre rations with others.

In July 1941, three prisoners appeared to have escaped from the camp; as a result, the Deputy Commander of Auschwitz ordered 10 men to be chosen to be starved to death in an underground bunker.

When one of the selected men Franciszek Gajowniczek heard he was selected, he cried out “My wife! My children!” At this point, Kolbe volunteered to take his place.

The Nazi commander replied, “What does this Polish pig want?”

Father Kolbe pointed with his hand to the condemned Franciszek Gajowniczek and repeated: “I am a Catholic priest from Poland; I would like to take his place because he has a wife and children.”

Rather surprised, the commander accepted Kolbe in place of Gajowniczek. Gajowniczek later said:

“I could only thank him with my eyes. I was stunned and could hardly grasp what was going on. The immensity of it: I, the condemned, am to live and someone else willingly and voluntarily offers his life for me – a stranger. Is this some dream?

I was put back into my place without having had time to say anything to Maximilian Kolbe. I was saved. And I owe to him the fact that I could tell you all this. The news quickly spread all round the camp. It was the first and the last time that such an incident happened in the whole history of Auschwitz.”

Franciszek Gajowniczek would miraculously survive Auschwitz, and would later be present at Kolbe’s canonisation in 1982.

The men were led away to the underground bunker where they were to be starved to death. It is said that in the bunker, Kolbe would lead the men in prayer and singing hymns to Mary. When the guards checked the cell, Kolbe could be seen praying in the middle. Bruno Borgowiec, a Polish prisoner who was charged with serving the prisoner later gave a report of what he saw:

“The ten condemned to death went through terrible days. From the underground cell in which they were shut up there continually arose the echo of prayers and canticles. The man in charge of emptying the buckets of urine found them always empty. Thirst drove the prisoners to drink the contents. Since they had grown very weak, prayers were now only whispered. At every inspection, when almost all the others were now lying on the floor, Father Kolbe was seen kneeling or standing in the centre as he looked cheerfully in the face of the SS men.

Father Kolbe never asked for anything and did not complain, rather he encouraged the others, saying that the fugitive might be found and then they would all be freed. One of the SS guards remarked: this priest is really a great man. We have never seen anyone like him…”

After two weeks, nearly all the prisoners, except Kolbe had died due to dehydration and starvation. Because the guards wanted the cell emptied, the remaining prisoners and Kolbe were executed with a lethal injection. Those present say he calmly accepted death, lifting up his arm. His remains were unceremoniously cremated on 15 August 1941.

The deed and courage of Maximillian Kolbe spread around the Auschwitz prisoners, offering a rare glimpse of light and human dignity in the face of extreme cruelty. After the war, his reputation grew and he became symbolic of courageous dignity.

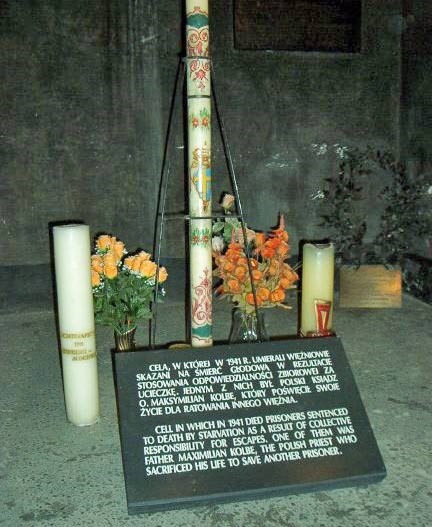

Photo of cell where Kolbe was executed

Kolbe was beatified as Confessor of the Faith in 1971. He was canonised as a martyr by Pope John Paul II (who himself lived through the German occupation of Poland) in 1981.

Pope John Paul II decided that Kolbe should be recognised as a martyr because the systematic hatred of the Nazi regime was inherently an act of hatred against religious faith, meaning Kolbe’s death equated to martyrdom. At his canonisation, in 1982 Pope John Paul II said:

“Maximilian did not die but gave his life … for his brother.”

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan. “Biography of Maximilian Kolbe”, Oxford, UK – www.biographyonline.net. 3rd AuguSaint 2014. Updated 2 March 2019.